[The following is a guest post from author and journalist Beth Winegarner. Winegarner’s latest book is “The Columbine Effect: How Five Teen Pastimes Got Caught in The Crossfire and Why Teens Are Taking Them Back.”]

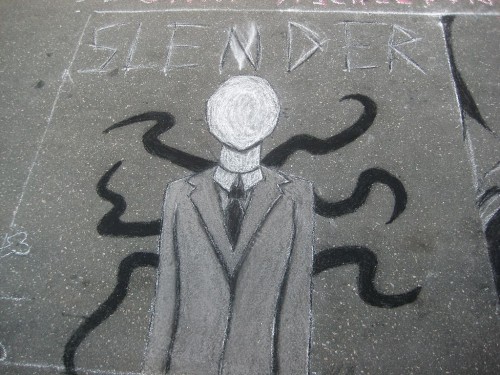

On May 31, news broke that two 12-year-old Milwaukee girls, Anissa Weier and Morgan Geyser, had stabbed a classmate 19 times and left her in the woods to die. Although those facts are startling enough on their own, much of the coverage has focused on the girls’ purported reason for the attack: they said they did it to appease the Slender Man, a fictional Internet character originally created by Eric Knudsen in 2009 during a Something Awful challenge. The Slender Man — or Slenderman, as he’s sometimes called — later joined the ranks on Creepypasta’s wiki catalog of fictional characters. Here’s what the site says about him:

Much of the fascination with Slender Man is rooted in the overall aura of mystery that he is wrapped in. Despite the fact that it is rumored he kills children almost exclusively, it is difficult to say whether or not his only objective is slaughter. Often times it is either reported or recorded that he can be found in sections of woods, and these generally tend to be suburban. He also has been reported seen with large groups of children, as many photographs portray. It is commonly thought that he resides in woods and forests and preys on children. He seems unconcerned with being exposed in the daylight or captured in photos.

The Slender Man story is a kind of fakelore; such stories have been since around long before the Internet. But in the days following the Wisconsin attack, some parents began demanding that Creepypasta either censor the article or shut down the site. Perhaps inevitably, in the days following the stabbing, some news outlets began targeting parents, asking if they know what their kids are looking at online. But such articles tend not to be too helpful. This one is full of vague half-statements about how kids always wind up in the “creepiest places” online, but offers few credible, concrete answers.

Such approaches to the attack suggest that the Internet in general, and the Slender Man story in particular, are to blame. Put another way, they imply that without Creepypasta’s wiki, the girls never would have stabbed their classmate. Even the mainstream press has done everything it can to connect the Milwaukee stabbing with the Slender Man story in readers’ minds: most are referring to it as the “Slenderman stabbing” now. In other places, headlines have made clear what they want readers to think: “Fantasy ‘Slender Man’ Meme Inspires Horrific Wisconsin Stabbing,” “Demonic Creature ‘Slender Man’ Motive For Waukesha Teen Stabbing?” “Could a fictional Internet character drive kids to kill?”

Even the Chicago Tribune, in the attempt to provide a more thoughtful piece on the killings, quickly concludes that children can lose the “boundary between fantasy and reality” when exposed to online fantasy violence, that 12-year-olds don’t understand that killing someone is permanent, and that “research confirms … that virtual violence raises anxiety and desensitizes kids to human suffering.” While it at least establishes that these kinds of events happened before Creepypasta, it plays up the shadowy specter that even young kids might become violent at any moment (which is true, but also incredibly rare). At the same time, it offers a seemingly simple solution: that if parents “restrict and monitor their kids’ Internet usage,” things will be just fine.

A writer for CNN Parents wrote an article discussing how parents can tell when their children are having trouble distinguishing fantasy from reality. It talks with a variety of experts, but when you examine their language, even they seem to be doing little more than guessing what might have led these two girls to attempt murder: “It may be kind of an inability to hold the potential consequences and reality in mind.” “”I think it’s the chemistry between these two girls. It was insane.”

Just about every time a teen or young adult commits a violent and seemingly senseless crime, society turns to media influences for an explanation. Whether it’s video games, extreme music, paganism, occultism or scary stories, it’s always some external factor — not the young perpetrator — that bears the bulk of the blame. The second scapegoat, particularly with younger kids or kids with developmental delays (like Adam Lanza) is their parents. As the news cycle on this stabbing matures, attention has now turned to Morgan Geyser’s father, who is allegedly fond of goth and metal cultures and who was also interested in Slender Man. But you can’t blame a man with countercultural interests — and who shares those interests with his daughter — for a killing. Not on that basis alone. There are far too many counter-examples.

The girls’ own attorney has openly acknowledged that they should undergo psychiatric evaluation. While “mental illness” is even more vague than “Slender Man” as an explanation, at least it begins the inquiry with the perpetrator. But others, including Joseph Laycock, have suggested that the girls aren’t mentally ill exactly: he cites other sources who say the intensity of their friendship might have been the spark for the crime, or that they simply blamed their acts on Slender Man to convince the police to go easier on them. Then he offers his own take:

I submit that Geyser and Weier were engaged in a form of play that extended the Slender Man legend complex through performance. Then, in a moment of lowered inhibitions, irrevocable consequences occurred, making the play world real. … The girls’ fascination with Slender Man was performative. Anna Freud noted that children often pretend to be monsters, acting out the very thing that they fear.

This difficult-to-comprehend crime comes on the heels of at least two others, including Elliot Rodgers’ rampage in Southern California and Miranda Barbour’s self-professed killing spree, which still hasn’t been proven. In Barbour’s case, she claimed she was a member of a Satanic cult. Journalists and police were correctly skeptical of Barbour’s claims, and that seems like an appropriate model for how we might approach the Wisconsin stabbing, too. In the wake of Rodgers’ spree, writer Mark Manson connected some of the dots on prior incidents of youth violence, from Columbine to Isla Vista, and came to an extremely important point about all of them: Nobody listened closely enough. He says:

Despite being relevant and important discussions, the glamorous headlines are ultimately distractions — they just feed into the carnage and the attention and the fame the killer desired. They are distractions from what is right in front of you and me and the victims of tomorrow’s shooting: people who need help. And while we’re all fighting over whose pet cause is more right and more true and more noble, there’s likely another young man out there, maybe suicidally depressed, maybe paranoid and delusional, maybe a psychopath, and he’s researching guns and bombs and mapping out schools and recording videos and thinking every day about the anger and hate he feels for this world. And no one is paying attention to him.